I often get emails asking that I share more of the history of the Sneeds in America. I'm always happy to oblige, because the Sneeds have a storied history.

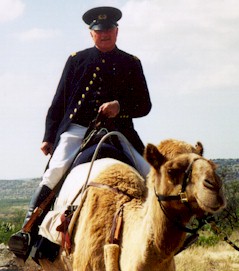

Our trip to the zoo this past weekend put me in mind of a story that my grandfather told me about his grandfather, Garret (Van)Sneed, who was born in Albany, NY, around 1820.

Garret's father was Jurean Van Sneed, a minister known for his stern ways. One day he caught sixteen-year-old Garret in a cornfield with the young daughter of a wealthy merchant. Both families were mortified. Garret was not considered a suitable marriage prospect, so the merchant demanded amends in another way. Garret was given a public flogging before the townsfolk. He was banished to a small cabin outside of the town, in the custody of a bachelor farmer, who farmed the merchant's land.

Two year's of servitude was the price extracted in addition to the beating.

Young Garret figured that hanging around a smelly old guy, with a serious penchant for hard work had little future and soon took flight. He signed on as a helper on a trapping expedition headed west. Over the next few years he trekked around northern Michigan, learning the trapping trade. What he learned was that trapping didn't agree with him. It mostly involved getting wet, cold and dirty, and trapping and skinning stinking animals in harsh, primative conditions.

Garret's trapping experience wasn't a complete loss though. It taught him the value of a keen eye and the ability to move across the landscape without being detected. Skills that would prove useful.

One day, while the trappers negotiated the sale of some pelts to an army platoon, Garret stuck up a conversation with one of the officers. They quickly made a deal for Garret to become a scout for the unit, playing on his outdoors skills. Although the trappers objected to the plan, the army had them outgunned and outnumbered, so they bade Garret godspeed, albeit grudgingly.

The platoon headed south into the lower Midwest and ultimately received orders to go to Texas to protect the growing population there. It was 1850 and Garret was around 30 years old.

Garret made the acquaintance of Henry Wayne, a young Army officer who was convinced that camels were the future for the army's burgeoning need to move supplies and equipment. The problem was finding someone to encourage the army brass to endorse the idea. Wayne caught the ear of Jefferson Davis, Senator from Mississippi and future president of the Confederacy. Davis was intrigued but wasn't sure he could deliver.

In the mean time, a plan began to develop around the camp. Someone proposed the idea that if a couple of enterprising fellows could raise the $20,000 or so needed to buy the camels, they could be resold to the army at a huge profit, once the idea was approved. Garret and two of his pals quit the army and over the next year or they barnstormed the small towns of Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana and Georgia, pitching their idea to investors and collecting small investments from hundreds of eager citizens hoping to cash in. Garret promised handsome returns to the yokels.

By 1855 Garret and his pals had raised the money needed, contracted with a ship's captain and set sail to the middle east to procure the camels, leaving from the Port of New Orleans.

Unfortunately for Garret and his mates, Jefferson Davis had been appointed Secretary of War and obtained the money needed to obtain camels for the army. The animals arrived in Indianola, Texas in 1856, and were put to work. Garret and his team trekked across north Africa in search of a suitable supplier of camels. They eventually found their treasure in Egypt and set sail for Texas, with 40 animals and 6 drovers in hand.

Meanwhile in Texas, trouble raised its ugly head. Davis and Major Wayne had a row over the matter of breeding the camel stock that they had. Wayne wanted to increase the herd and Davis figured that they had all the camels they needed. Wayne got pissed and transferred leaving the camels to commanders who were not enamored of them. The new commanders learned that camels are an acquired taste. They tend to be smelly, ill-tempered and stubborn.

Eventually Davis ordered that the use of camels to haul supplies be halted. The animals languished in their pens. Even though they later distinguished themselves for a short time during westward exploration, the army's experiment with camels has passed it's peak.

In 1857, about the time that the great experiment was winding down, Garret and his caravan reached Indianola, having travelled overland from New Orleans. The trip overland took longer than expected. In fact, many times camels got loose and would lumber off across the countryside with Garret and his party in pursuit. In order to recapture them, the pursuers would have to dismount and sneak up on the beast when it paused to rest. Often this meant walking a considerable distance, which is where the expression, "I'd walk a mile for a camel" actually comes from.

Upon arriving at Indianola, Garret had 38 animals and the six drovers, two camels had vanished, never to be found. Unfortunately, the army no longer wanted the camels and he was left with a herd of eating machines and their bewildered handlers.

Garret surveyed the situation, weighed his options and decided to skip town, leaving his charges to figure things out for themselves. Some animals were sold or given to locals, others died of neglect, some vanished into the desert and some were tried in private business. Garret headed north, arriving in Albany, where he made amends with his family and took a job as a shopkeeper's assistant. He continued to dream of a better life.

One day, while visiting New York, where he hoped to interest some businessmen in his idea for an improved plow, he bumped in to a Mr. Joshua Johnson, of Macon, Georgia, who recognized him as the fellow who took several hundred dollars from the good citizens of Macon to buy camels. Johnson demanded that Garret return the money and when he refused, Johnson shot him in the upper thigh. Garret lingered in a local hospital for a couple of weeks, before succumbing to infection.

As always with the Sneeds in America, if its not totally bad ideas that do us in, its good ones that are just a bit past their time. Or as the family crest proudly proclaims, Illegitimi non carborundum (Don't let the bastards grind you down).

Merle.

Things in this blog represented to be fact, may or may not actually be true. The writer is frequently wrong, sometimes just full of it, but always judgemental and cranky

Tag: Daily Life

Personal Finance

Humor

I often get emails asking that I share more of the history of the Sneeds in America. I'm always happy to oblige, because the Sneeds have a storied history.

Our trip to the zoo this past weekend put me in mind of a story that my grandfather told me about his grandfather, Garret (Van)Sneed, who was born in Albany, NY, around 1820.

Garret's father was Jurean Van Sneed, a minister known for his stern ways. One day he caught sixteen-year-old Garret in a cornfield with the young daughter of a wealthy merchant. Both families were mortified. Garret was not considered a suitable marriage prospect, so the merchant demanded amends in another way. Garret was given a public flogging before the townsfolk. He was banished to a small cabin outside of the town, in the custody of a bachelor farmer, who farmed the merchant's land.

Two year's of servitude was the price extracted in addition to the beating.

Young Garret figured that hanging around a smelly old guy, with a serious penchant for hard work had little future and soon took flight. He signed on as a helper on a trapping expedition headed west. Over the next few years he trekked around northern Michigan, learning the trapping trade. What he learned was that trapping didn't agree with him. It mostly involved getting wet, cold and dirty, and trapping and skinning stinking animals in harsh, primative conditions.

Garret's trapping experience wasn't a complete loss though. It taught him the value of a keen eye and the ability to move across the landscape without being detected. Skills that would prove useful.

One day, while the trappers negotiated the sale of some pelts to an army platoon, Garret stuck up a conversation with one of the officers. They quickly made a deal for Garret to become a scout for the unit, playing on his outdoors skills. Although the trappers objected to the plan, the army had them outgunned and outnumbered, so they bade Garret godspeed, albeit grudgingly.

The platoon headed south into the lower Midwest and ultimately received orders to go to Texas to protect the growing population there. It was 1850 and Garret was around 30 years old.

Garret made the acquaintance of Henry Wayne, a young Army officer who was convinced that camels were the future for the army's burgeoning need to move supplies and equipment. The problem was finding someone to encourage the army brass to endorse the idea. Wayne caught the ear of Jefferson Davis, Senator from Mississippi and future president of the Confederacy. Davis was intrigued but wasn't sure he could deliver.

In the mean time, a plan began to develop around the camp. Someone proposed the idea that if a couple of enterprising fellows could raise the $20,000 or so needed to buy the camels, they could be resold to the army at a huge profit, once the idea was approved. Garret and two of his pals quit the army and over the next year or they barnstormed the small towns of Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana and Georgia, pitching their idea to investors and collecting small investments from hundreds of eager citizens hoping to cash in. Garret promised handsome returns to the yokels.

By 1855 Garret and his pals had raised the money needed, contracted with a ship's captain and set sail to the middle east to procure the camels, leaving from the Port of New Orleans.

Unfortunately for Garret and his mates, Jefferson Davis had been appointed Secretary of War and obtained the money needed to obtain camels for the army. The animals arrived in Indianola, Texas in 1856, and were put to work. Garret and his team trekked across north Africa in search of a suitable supplier of camels. They eventually found their treasure in Egypt and set sail for Texas, with 40 animals and 6 drovers in hand.

Meanwhile in Texas, trouble raised its ugly head. Davis and Major Wayne had a row over the matter of breeding the camel stock that they had. Wayne wanted to increase the herd and Davis figured that they had all the camels they needed. Wayne got pissed and transferred leaving the camels to commanders who were not enamored of them. The new commanders learned that camels are an acquired taste. They tend to be smelly, ill-tempered and stubborn.

Eventually Davis ordered that the use of camels to haul supplies be halted. The animals languished in their pens. Even though they later distinguished themselves for a short time during westward exploration, the army's experiment with camels has passed it's peak.

In 1857, about the time that the great experiment was winding down, Garret and his caravan reached Indianola, having travelled overland from New Orleans. The trip overland took longer than expected. In fact, many times camels got loose and would lumber off across the countryside with Garret and his party in pursuit. In order to recapture them, the pursuers would have to dismount and sneak up on the beast when it paused to rest. Often this meant walking a considerable distance, which is where the expression, "I'd walk a mile for a camel" actually comes from.

Upon arriving at Indianola, Garret had 38 animals and the six drovers, two camels had vanished, never to be found. Unfortunately, the army no longer wanted the camels and he was left with a herd of eating machines and their bewildered handlers.

Garret surveyed the situation, weighed his options and decided to skip town, leaving his charges to figure things out for themselves. Some animals were sold or given to locals, others died of neglect, some vanished into the desert and some were tried in private business. Garret headed north, arriving in Albany, where he made amends with his family and took a job as a shopkeeper's assistant. He continued to dream of a better life.

One day, while visiting New York, where he hoped to interest some businessmen in his idea for an improved plow, he bumped in to a Mr. Joshua Johnson, of Macon, Georgia, who recognized him as the fellow who took several hundred dollars from the good citizens of Macon to buy camels. Johnson demanded that Garret return the money and when he refused, Johnson shot him in the upper thigh. Garret lingered in a local hospital for a couple of weeks, before succumbing to infection.

As always with the Sneeds in America, if its not totally bad ideas that do us in, its good ones that are just a bit past their time. Or as the family crest proudly proclaims, Illegitimi non carborundum (Don't let the bastards grind you down).

Merle.

Things in this blog represented to be fact, may or may not actually be true. The writer is frequently wrong, sometimes just full of it, but always judgemental and cranky

Tag: Daily Life

Personal Finance

Humor

Nov 21, 2006

Another Fine Mess

I often get emails asking that I share more of the history of the Sneeds in America. I'm always happy to oblige, because the Sneeds have a storied history.

Our trip to the zoo this past weekend put me in mind of a story that my grandfather told me about his grandfather, Garret (Van)Sneed, who was born in Albany, NY, around 1820.

Garret's father was Jurean Van Sneed, a minister known for his stern ways. One day he caught sixteen-year-old Garret in a cornfield with the young daughter of a wealthy merchant. Both families were mortified. Garret was not considered a suitable marriage prospect, so the merchant demanded amends in another way. Garret was given a public flogging before the townsfolk. He was banished to a small cabin outside of the town, in the custody of a bachelor farmer, who farmed the merchant's land.

Two year's of servitude was the price extracted in addition to the beating.

Young Garret figured that hanging around a smelly old guy, with a serious penchant for hard work had little future and soon took flight. He signed on as a helper on a trapping expedition headed west. Over the next few years he trekked around northern Michigan, learning the trapping trade. What he learned was that trapping didn't agree with him. It mostly involved getting wet, cold and dirty, and trapping and skinning stinking animals in harsh, primative conditions.

Garret's trapping experience wasn't a complete loss though. It taught him the value of a keen eye and the ability to move across the landscape without being detected. Skills that would prove useful.

One day, while the trappers negotiated the sale of some pelts to an army platoon, Garret stuck up a conversation with one of the officers. They quickly made a deal for Garret to become a scout for the unit, playing on his outdoors skills. Although the trappers objected to the plan, the army had them outgunned and outnumbered, so they bade Garret godspeed, albeit grudgingly.

The platoon headed south into the lower Midwest and ultimately received orders to go to Texas to protect the growing population there. It was 1850 and Garret was around 30 years old.

Garret made the acquaintance of Henry Wayne, a young Army officer who was convinced that camels were the future for the army's burgeoning need to move supplies and equipment. The problem was finding someone to encourage the army brass to endorse the idea. Wayne caught the ear of Jefferson Davis, Senator from Mississippi and future president of the Confederacy. Davis was intrigued but wasn't sure he could deliver.

In the mean time, a plan began to develop around the camp. Someone proposed the idea that if a couple of enterprising fellows could raise the $20,000 or so needed to buy the camels, they could be resold to the army at a huge profit, once the idea was approved. Garret and two of his pals quit the army and over the next year or they barnstormed the small towns of Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana and Georgia, pitching their idea to investors and collecting small investments from hundreds of eager citizens hoping to cash in. Garret promised handsome returns to the yokels.

By 1855 Garret and his pals had raised the money needed, contracted with a ship's captain and set sail to the middle east to procure the camels, leaving from the Port of New Orleans.

Unfortunately for Garret and his mates, Jefferson Davis had been appointed Secretary of War and obtained the money needed to obtain camels for the army. The animals arrived in Indianola, Texas in 1856, and were put to work. Garret and his team trekked across north Africa in search of a suitable supplier of camels. They eventually found their treasure in Egypt and set sail for Texas, with 40 animals and 6 drovers in hand.

Meanwhile in Texas, trouble raised its ugly head. Davis and Major Wayne had a row over the matter of breeding the camel stock that they had. Wayne wanted to increase the herd and Davis figured that they had all the camels they needed. Wayne got pissed and transferred leaving the camels to commanders who were not enamored of them. The new commanders learned that camels are an acquired taste. They tend to be smelly, ill-tempered and stubborn.

Eventually Davis ordered that the use of camels to haul supplies be halted. The animals languished in their pens. Even though they later distinguished themselves for a short time during westward exploration, the army's experiment with camels has passed it's peak.

In 1857, about the time that the great experiment was winding down, Garret and his caravan reached Indianola, having travelled overland from New Orleans. The trip overland took longer than expected. In fact, many times camels got loose and would lumber off across the countryside with Garret and his party in pursuit. In order to recapture them, the pursuers would have to dismount and sneak up on the beast when it paused to rest. Often this meant walking a considerable distance, which is where the expression, "I'd walk a mile for a camel" actually comes from.

Upon arriving at Indianola, Garret had 38 animals and the six drovers, two camels had vanished, never to be found. Unfortunately, the army no longer wanted the camels and he was left with a herd of eating machines and their bewildered handlers.

Garret surveyed the situation, weighed his options and decided to skip town, leaving his charges to figure things out for themselves. Some animals were sold or given to locals, others died of neglect, some vanished into the desert and some were tried in private business. Garret headed north, arriving in Albany, where he made amends with his family and took a job as a shopkeeper's assistant. He continued to dream of a better life.

One day, while visiting New York, where he hoped to interest some businessmen in his idea for an improved plow, he bumped in to a Mr. Joshua Johnson, of Macon, Georgia, who recognized him as the fellow who took several hundred dollars from the good citizens of Macon to buy camels. Johnson demanded that Garret return the money and when he refused, Johnson shot him in the upper thigh. Garret lingered in a local hospital for a couple of weeks, before succumbing to infection.

As always with the Sneeds in America, if its not totally bad ideas that do us in, its good ones that are just a bit past their time. Or as the family crest proudly proclaims, Illegitimi non carborundum (Don't let the bastards grind you down).

Merle.

Things in this blog represented to be fact, may or may not actually be true. The writer is frequently wrong, sometimes just full of it, but always judgemental and cranky

Tag: Daily Life

Personal Finance

Humor

I often get emails asking that I share more of the history of the Sneeds in America. I'm always happy to oblige, because the Sneeds have a storied history.

Our trip to the zoo this past weekend put me in mind of a story that my grandfather told me about his grandfather, Garret (Van)Sneed, who was born in Albany, NY, around 1820.

Garret's father was Jurean Van Sneed, a minister known for his stern ways. One day he caught sixteen-year-old Garret in a cornfield with the young daughter of a wealthy merchant. Both families were mortified. Garret was not considered a suitable marriage prospect, so the merchant demanded amends in another way. Garret was given a public flogging before the townsfolk. He was banished to a small cabin outside of the town, in the custody of a bachelor farmer, who farmed the merchant's land.

Two year's of servitude was the price extracted in addition to the beating.

Young Garret figured that hanging around a smelly old guy, with a serious penchant for hard work had little future and soon took flight. He signed on as a helper on a trapping expedition headed west. Over the next few years he trekked around northern Michigan, learning the trapping trade. What he learned was that trapping didn't agree with him. It mostly involved getting wet, cold and dirty, and trapping and skinning stinking animals in harsh, primative conditions.

Garret's trapping experience wasn't a complete loss though. It taught him the value of a keen eye and the ability to move across the landscape without being detected. Skills that would prove useful.

One day, while the trappers negotiated the sale of some pelts to an army platoon, Garret stuck up a conversation with one of the officers. They quickly made a deal for Garret to become a scout for the unit, playing on his outdoors skills. Although the trappers objected to the plan, the army had them outgunned and outnumbered, so they bade Garret godspeed, albeit grudgingly.

The platoon headed south into the lower Midwest and ultimately received orders to go to Texas to protect the growing population there. It was 1850 and Garret was around 30 years old.

Garret made the acquaintance of Henry Wayne, a young Army officer who was convinced that camels were the future for the army's burgeoning need to move supplies and equipment. The problem was finding someone to encourage the army brass to endorse the idea. Wayne caught the ear of Jefferson Davis, Senator from Mississippi and future president of the Confederacy. Davis was intrigued but wasn't sure he could deliver.

In the mean time, a plan began to develop around the camp. Someone proposed the idea that if a couple of enterprising fellows could raise the $20,000 or so needed to buy the camels, they could be resold to the army at a huge profit, once the idea was approved. Garret and two of his pals quit the army and over the next year or they barnstormed the small towns of Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana and Georgia, pitching their idea to investors and collecting small investments from hundreds of eager citizens hoping to cash in. Garret promised handsome returns to the yokels.

By 1855 Garret and his pals had raised the money needed, contracted with a ship's captain and set sail to the middle east to procure the camels, leaving from the Port of New Orleans.

Unfortunately for Garret and his mates, Jefferson Davis had been appointed Secretary of War and obtained the money needed to obtain camels for the army. The animals arrived in Indianola, Texas in 1856, and were put to work. Garret and his team trekked across north Africa in search of a suitable supplier of camels. They eventually found their treasure in Egypt and set sail for Texas, with 40 animals and 6 drovers in hand.

Meanwhile in Texas, trouble raised its ugly head. Davis and Major Wayne had a row over the matter of breeding the camel stock that they had. Wayne wanted to increase the herd and Davis figured that they had all the camels they needed. Wayne got pissed and transferred leaving the camels to commanders who were not enamored of them. The new commanders learned that camels are an acquired taste. They tend to be smelly, ill-tempered and stubborn.

Eventually Davis ordered that the use of camels to haul supplies be halted. The animals languished in their pens. Even though they later distinguished themselves for a short time during westward exploration, the army's experiment with camels has passed it's peak.

In 1857, about the time that the great experiment was winding down, Garret and his caravan reached Indianola, having travelled overland from New Orleans. The trip overland took longer than expected. In fact, many times camels got loose and would lumber off across the countryside with Garret and his party in pursuit. In order to recapture them, the pursuers would have to dismount and sneak up on the beast when it paused to rest. Often this meant walking a considerable distance, which is where the expression, "I'd walk a mile for a camel" actually comes from.

Upon arriving at Indianola, Garret had 38 animals and the six drovers, two camels had vanished, never to be found. Unfortunately, the army no longer wanted the camels and he was left with a herd of eating machines and their bewildered handlers.

Garret surveyed the situation, weighed his options and decided to skip town, leaving his charges to figure things out for themselves. Some animals were sold or given to locals, others died of neglect, some vanished into the desert and some were tried in private business. Garret headed north, arriving in Albany, where he made amends with his family and took a job as a shopkeeper's assistant. He continued to dream of a better life.

One day, while visiting New York, where he hoped to interest some businessmen in his idea for an improved plow, he bumped in to a Mr. Joshua Johnson, of Macon, Georgia, who recognized him as the fellow who took several hundred dollars from the good citizens of Macon to buy camels. Johnson demanded that Garret return the money and when he refused, Johnson shot him in the upper thigh. Garret lingered in a local hospital for a couple of weeks, before succumbing to infection.

As always with the Sneeds in America, if its not totally bad ideas that do us in, its good ones that are just a bit past their time. Or as the family crest proudly proclaims, Illegitimi non carborundum (Don't let the bastards grind you down).

Merle.

Things in this blog represented to be fact, may or may not actually be true. The writer is frequently wrong, sometimes just full of it, but always judgemental and cranky

Tag: Daily Life

Personal Finance

Humor

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment